Deng Xiaoping is frequently credited to have been the most productive leader of China since the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1954. Overshadowing Mao Zedong, the previous leader of the PRC, remembered by the world as a tyrannical dictator who resulted in the deaths of millions, Deng has been praised internationally as the man who brought the People's Republic of China into its modern stage of rapid growth and accelerated development. There may be no doubt about at least one of Deng’s feats: He brought industrialization and agricultural growth into the urban areas of China extremely rapidly, comparatively when considering the lagging agricultural development of the First Five Year Plan (which otherwise saw extremely strong growth) [1], which was based largely upon the model of the Chinese nationalists (the Kuomintang) [2], or the Second Five Year Plan (the Great Leap Forward of Mao Zedong).

Due to the incompetence of Mao Zedong, who instigated the failed “Four Pests Campaign”, and ineffective backyard burnings of metal in the Great Leap Forward, Deng Xiaoping’s atrocities are often overlooked, and his administration is seen for the first time in the more recent Chinese history, as a step in the right direction. This perception of Deng Xiaoping is completely in error. Deng’s administration was responsible for the deaths of hundreds of thousands of scores of his own citizens, which could have otherwise been avoided. His economic reforms have left much of rural China struggling to catch up to the urban and developed centers of China. His systemic legacy has caused the slow erasure of Chinese rural culture due to incentivized assimilation of farmers. Deng was responsible for massacres too often forgotten. Not too different however, from his predecessor, Deng had been quick to crack down on dissenting voices, including strikes. These claims will all be substantiated within the course of the analysis.

Labor Rights

There have been multiple different versions of the constitution passed within the PRC in 1954, 1975, 1978, and 1982. The 1954 Constitution had no legislation relating to the right to strike, however, during the succeeding versions of the constitution, the right to strike in China was finally guaranteed, in Article 28 of the 1975 constitution, and Article 45 of the 1978 constitution. See the following excerpts:

“ARTICLE 28 Citizens enjoy freedom of speech, correspondence, the press, assembly, association, procession, demonstration and the freedom to strike, and enjoy freedom to believe in religion and freedom not to believe in religion and to propagate atheism.

Article 45 Citizens enjoy freedom of speech, correspondence, the press, assembly, association, procession, demonstration and the freedom to strike, and have the right to "speak out freely, air their views fully, hold great debates and write big-character posters".

The progressive path which China was achieving in this regard was stunted by the 1982 Constitution under Deng Xiaoping, in which the right to strike was officially removed from the Chinese constitution, and the article guaranteeing basic rights of freedom of speech, press, assembly, association, procession and demonstration, now excludes the right to strike. This form of the constitution is the form which is enacted in China to this day (2024). The biggest question surrounding this controversial step backwards is “Why?” One would suppose that the most likely reason as to why strikes were removed as a right was an action taken in response to the “wave of democratic movement”, as Chang and Cooke (2015), suppose in their paper on the matter [3]. Being that the state has an incentive to expand their power, removing the right to strike would be an extremely important move for them to carry out, and indeed it was. Not explicitly outlawing strikes while maintaining that strikes are not a right that the people hold is influential in ensuring that the state can seem open and democratic superficially while legally being able to crack down on strikes whenever it sees such action fit. For reference, crackdowns on strikes were not even something which Mao Zedong saw fit to do, stating:

We should permit workers to strike, permit them to hold demonstrations. Our Constitution allows workers to hold demonstrations, and I propose we should add one article of freedom of strike when we amend our Constitution next time. It will help resolve the conflicts between the state, the director of the enterprise and the workers. (1956)

Accordingly, this right was added in the next rework of China’s constitutional framework.

Deng’s frequent excuse, which was lacking in principle, for any and all actions which he committed, was that China’s material conditions necessitated such legislation. There was no necessity in 1982, under any pretext, to remove the right for strikes. In fact, after this was passed, it could be observed throughout all of the 1980s that there was an increase in go-slows and strikes in China in both the private and public sector [3]. Deng did not put any thought into workers’ rights in a productive manner, because what Deng cared most about was economic growth. Deng’s obsession with economic growth would have long term systemic effects that to this day are detrimental to harmony within China, as will be argued in the following section.

The Urban-Rural Divide

The CCP under Deng decided to build more infrastructure along coastlines. The reason for this was that coastline developments would more readily attract investors and through this, China would be able to achieve much more rapid growth. This prediction was very well developed and brought about massive leaps in economic growth. Wealthy regions retained their wealth from foreign investments which then could be reintegrated into the development of the local communities [4]. There is, however, a shadow to these reforms, which allows today, the largest income divide in all of China, which is the divide between the rural and the developed sections of the nation. A massive discrepancy, which has seen only modest improvements, growing and shrinking at various points throughout the last forty years.

If China, instead of following Deng's model, allowed a more restrictive growth rate, and cared about people over profit, then they could have allowed for resources to have been diverted for support to the present poor rural areas. If this path was taken, then additional spending on healthcare and education could have been achieved. However, China was not a state for the people or by the people, and it shows. Continuing a growth rate around the lines of what even the Great Leap Forward was allowing for could have conceivably achieved the ability to divert resources in the rural regions, which could be argued from the perspective of certain heterodox economists such as Lippit, who argues, contrary to popular opinion, that China in fact gained a decade of growth under the GLF as it’s economic program [7]. China’s reforms under Deng and the related export boom caused a reduction in the purchasing power of the workers, which obviously has a disproportionate effect on the rural populations. The reduction in purchasing power is caused due to the lack of China’s “public provisioning system”, dismantled by Deng himself. With the removal of China’s public provisioning system, prices jumped for foods, leading to a necessary reduction in the consumption of China’s population. With the privatization of healthcare under Deng’s tenure, mortality rates stagnated within China, and did not progress well compared to many comparable developing nations, especially during the first half of the 1980s [8]. This can be seen most prominently in the rural regions, in which the amount of healthcare workers dramatically decreased in response to the privatization of healthcare. As Dreze & Sen (1989) [10] point out, this was a large driving factor in the increase of especially child/infant mortality rates, and a decrease in life expectancy [8].

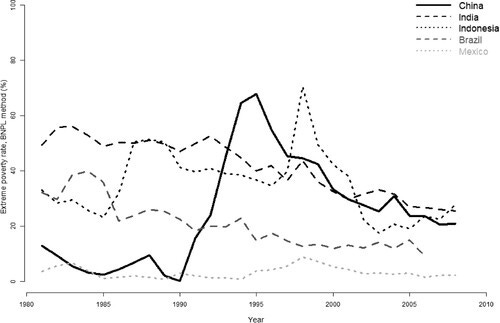

Sullivan, Moatsos, and Hickel (2023), show that extreme poverty, contrary to the World Bank’s projections, did not in fact go down during the “Dengist” reform period, but rather that extreme poverty increased during Deng’s reform period, and was rather overestimated by the World Bank during the pre-Deng period. [8]

Moatsos, M., 2021. Global extreme poverty: present and past since 1820. In: OECD, ed. How was life? Vol. II: new perspectives on well-being and global inequality since 1820. Paris: OECD Publishing, 186–212.

The reason for this miscalculation is because the World Bank measures the poverty line by $1.90 a day, not taking into account the purchasing power of the workers, which, as has been stated previously, decreased during the reform period. Nor does this take into account a “basic needs'' metric. Professor of Economic History, Robert C Allen, has designed and put forward a poverty line on the basis of a basic needs list [9], which is measured based on the purchasing price (according to Sullivan, Moatsos & Hickel (2023)) of “2,100 calories per day, plus 50 g of protein, 34 g of fat, various vitamins and minerals, some clothing and heating, and 3 square meters of housing” [8]. Based on Allen’s basic needs poverty line, we find that China’s poverty rate would have been 68% in 1995, an all-time peak throughout the last fifteen or more years. China’s poverty rate slowly recovered, though even as of 2018 (5.4% poverty rate) it seems as though China’s poverty rate is still at the level it was at throughout the 1980s (5.6% poverty rate) [8]. With these metrics, China’s claim to be alleviating poverty to any incredible degree completely collapses– And chairman Deng Xiaoping can be thanked entirely for that.

If Deng wanted to set up his reforms for a slower rate of growth, then he undoubtedly would have done more to improve education and healthcare within the poorer, rural regions. Instead, Deng allowed localities to retain a large share of the income they generate, diminishing the resources that flow to the center, and of course, local officials know that by developing projects in their provinces, they will be able to advance their careers, and thus they are not incentivized at all by the Chinese political system to leave more income to citizens or to expand social welfare. Because of this now, the government has less money for social welfare as well as less money to support the poorer, rural regions, even if they really did want to. Accordingly, little oversight in regard to resource allocation leaves the door open to intense corruption.

Human Rights Abuses

Deng Xiaoping was responsible for countless senseless killings of his own citizens. Undoubtedly, the murder of your own citizens is the greatest crime which a national leader, responsible for the safety of his citizens, can commit. There is importance in mentioning the invasion of Tibet (which occurred under the ultranationalist irredentist position, laid forward by Deng Xiaoping that Tibet was an integral part of Chinese territory which must be invaded) which resulted in hundreds of unnecessary civilian deaths [12], and was later downplayed by the Chinese government as the “Peaceful Liberation of Tibet” [13]. Deng ought to be blamed in the fullest for this imperialist movement upon the Tibetan people who violently resisted the Chinese expansionist project. Nothing mentioned here will be of any use in discouraging modern “Dengists” who have no cares or concerns for human rights. Deng referred to protestors who advocated for democracy as the “scum of the Chinese nation” (despite the party’s initial stance that protest should be allowed) [14] and his modern sycophantic lickspittles toe the line on this point.

It wouldn’t be until 1991 when the CCP would finally accept human rights as compatible with Chinese socialism, a long delay, and only after Deng Xiaoping was gone from public office permanently after having stepped down from his position as the Chairman of the Central Military Commission in 1990. The 1989 Tiananmen square protests were emblematic of Deng Xiaoping’s approach to political domination, as when protests erupted within the country, handfuls of people were massacred in central Beijing near the square, as has been thoroughly documented by eyewitnesses [15]. On-the-scene reporters documented around 400 deaths [16] while the Chinese government itself reported at the very least, 200 non-soldier deaths, while the number of Chinese soldiers who died in this confrontation according to the same report, was minimal [17]. The Chinese government has gone out of its way to lie regarding this incident, claiming that the protestors used petrol bombs which forced the soldiers to open fire on the crowds. Document 12 [18] from the National Security Archive’s Tiananmen Papers have thoroughly debunked this stupidly unthoughtful argument through the following excerpts:

Troops using automatic weapons advanced in tanks, APCs, and trucks from several directions on Tiananmen Square June 3rd. There was considerable resistance by demonstrators, and the number of casualties appears high. … American citizens… were severely beaten by Chinese troops on Tiananmen Square. Their cameras were smashed and they were dragged into The Great Hall of The People. … hospitals are said to be overwhelmed by casualties…

This demonstrates not only that through the scale of military response, the Chinese crackdown was without doubt premeditated, that Chinese troops not only attacked Chinese protestors, but also attacked American nationals indiscriminately who were reporting on the situation, while the filling of hospitals with casualties also contradicts the Chinese government’s claim that casualties that day were low.

As well, the fact is that martial law had been implemented in China on the 20th of May which was intended to stop strikes and anything which could possibly lead to social unrest in the country, which is why the military was deployed in the first place at Tiananmen square and authorized to adopt any means to forcefully handle matters, which is noted by Maurice Meisner in “The Deng Xiaoping era: an inquiry into the fate of Chinese socialism, 1978-1994” [19].

Deng Xiaoping’s one-child policy can also be thanked for the sharp rise in female infanticide in China [20] which had been dropping throughout the Maoist period, as the end of the Cultural Revolution brought about the return of traditional Chinese cultural values, which heavily devalued women— and it shows. Millions of infant females were killed by their parents over the course of decades as men were (and still are) favored in Chinese society [34]. Between 1980 and 2014, 109,000,000 Chinese women were sterilized and 324,000,000 received IUDs, almost entirely against their wills, as this was law [21]. This cruel reality may be seen by many as a necessity, as the track which the Chinese birth rate was on, many may argue, was going to create a food shortage due to overpopulation. This is false. As noted by Hesketh [22] in his study on the One-Child Policy, the voluntary education programs such as “Late, Long, Few”, had already succeeded, in the decade prior to the One-Child Policy of Deng Xiaoping, in reducing the fertility rates from 5.9 children per woman to 2.9 per woman. Education and health services were already well on the road to vastly and sufficiently easing China’s overpopulation issue. The modern “pragmatic left” and many of the Marxist-Leninists of today are to fully blame for the veneration of Deng Xiaoping’s abominable mutation of politics in the modern West, and ought to be condemned.

Deng Xiaoping’s Capitalism - Capitalism with Chinese Characteristics

China has laid claim to a form of socialism based upon “historical necessity” and “material conditions” which required its socialism to take the form of capitalism. This is its pathetic defense by which it has attempted to claim that it truly has not abandoned socialism. It refers to its version of socialism as “Socialism with Chinese Characteristics”. I have never met a single Marxist who believes that China is truly socialist who has been able to explain the “material conditions” which necessitated the partial privatization of healthcare and the dismantling of much of China’s public provisioning system.

The “dictatorship of the proletariat” envisioned as definitionally central to Marxist socialism is absent within the People’s Republic of China. The bourgeois controls Chinese politics. In 2013, the richest 3% of members of the National People’s Congress average net worth was $1.1 billion. In 2017, 20% of delegates were owners of corporations, while in 2018, 153 delegates had a combined wealth of $650,000,000,000. In 2019, 90 delegates within the National People’s Congress were among the top 1,000 most wealthy Chinese [23] [24] [25]. Any idiotic winging which claims that the National People’s Congress’ subjugation to the so-called “Communist Party” makes China socialist is silly. The CCP’s leadership is just as comprised of members of the bourgeois and career politicians as the National People’s Congress is. Xi Zhongxun, the father of Xi Jinping, the present President of the PRC, was a career politician in power since the 1950s, when he first became the 1st Secretary-General of the State Council.

Any statements which profess that China is simply “discovering its own way to socialism” are blinding themselves to the reality which we have watched for the last four decades unfold in China as it pursues more and more neoliberal reforms. Deng himself wasn’t quite sure what “socialism” was supposed to look like, as pointed out by Mao Zedong [26].

This person does not grasp class struggle; he has never referred to this key link. Still his theme of 'white cat, black cat', making no distinction between imperialism and Marxism. … He does not understand Marxism-Leninism, he represents the capitalist class.

Deng was more than willing to admit that he had absolutely no clue what he was supposed to be doing in developing the Chinese socialist project on more than one occasion [27].

Our basic goal — to build socialism — is correct, but we are still trying to figure out what socialism is and how to build it. The primary task for socialism is to develop the productive forces.

Deng Xiaoping showed his allegiances to the capitalist order in his rehabilitation of “capitalist roaders” such as Liu Shaoqi, who believed that an exploitative, parasitic and wealthy peasantry was necessary under socialism, stating [28] [29]:

At present, exploitation saves people, and it is dogmatic to forbid it. . . .Hiring of farmhands in industrial farming should be left to take their own course.... It is good if some rich peasants should emerge as a result.

Our policy to preserve the rich peasant economy is not a temporary measure, it is a long-term measure.

Liu Shaoqi was the Second Chairman of the People’s Republic of China and had staunch disagreements with Mao Zedong in many respects, who did not hope to see the capitalistic and pragmatist reforms which Liu had in mind, highly mistrusting him, leading to him being purged during the Cultural Revolution, as Mao Zedong was well aware that Shaoqi’s pragmatist faction would eventually lead China back down the road of capitalism. Deng, however, fell completely in line with Liu’s ideology, and believed that “the rehabilitation of Comrade Liu Shaoqi is a major matter and we have handled it very well” [30].

Deng was frequently hesitant to consider capitalism as something which ought to be denounced, choosing to reply to Italian journalist Oriana Fallaci, who asked him whether or not “capitalism is not all that bad”, with “We must distinguish what is capitalism. Capitalism is superior to feudalism.” There is no question-dodge clearer than this. Deng Xiaoping’s regime saw an end to socialism within China, however, his successors would only make conditions worse as the nation, both during and after his regime, opened itself up to foreign investment more and more— meaning that international capitalist interests now had direct control over Chinese economic development, ending any concept of national self-determination for good, as China’s development is reliant on foreign corporate involvement in China’s economy.

Deng Xiaoping, on September 4, 1989, in a conversation with the CPC Central Committee, made it clear that Jiang Zemin, the General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party, ought to be the next individual which the Central Committe orients itself around, stating “Comrade Jiang Zemin should become the core of your collective” and “I should like to propose that Comrade Jiang Zemin be appointed Chairman of the Central Military Commission.” Many blame Jiang Zemin for the excesses of the capitalist “features” of the Chinese economy, being reserved in their critiques of Deng, forgetting who propped Jiang Zemin up as the next great leader of China to the CCP [31].

Jiang Zemin was the most important leader of China between 1989 and 2003. He followed in Deng Xiaoping’s footsteps as the inheritor of his ideology and his spineless reforms. Jiang privatized countless SOEs, resulting in 40,000,000 individuals being laid off from work. Urban housing was privatized, resulting in many of the soulless corporate high-rises seen across China today. Farmers protested the new high tax-rates being implemented by the regime, and the millions of individuals who were left unemployed by Jiang Zemin’s privatizations joined in [32]. PNAS published a study which proved that between 1980 and 2002, the Gini coefficient in China had only increased, meaning that income inequality had risen significantly. Although Jiang’s reforms partially intended to distribute more wealth into the rural poor regions which were disaffected by Deng Xiaoping, this reality shows that Jiang’s attempts in his thirteen years in power bore no fruit in aiding the poor and disadvantaged in China [33]. Referencing Allen’s basic needs poverty line discussed earlier, the peak of Chinese poverty in 1995 was under Jiang’s continuation of Dengist policy.

The Legacy of Deng Xiaoping

Deng Xiaoping’s legacy is that of a crude developmentalism which lead to the detriment of the people of his nation. Skyrocketing poverty, forced sterilizations, an increasingly divergent relationship between the city and the countryside, rampant corruption both locally and nationally, and the introduction of the ‘dictatorship of the bourgeois’ in Chinese politics is what Deng Xiaoping leaves behind. Although some of these issues have seen improvements under the government of Xi Jinping in modern China, much remains the same, and the “People’s” Republic of China of today can still be identified as exactly what it was under Deng Xiaoping— a wolf in sheep’s clothing.

Sources

Kevin van Lengen, Sven. Economic Development of the People's Republic of China During the War Recovery Period & First Five-Year Plan. 2021

Kirby, William C. “Continuity and Change in Modern China: Economic Planning on the Mainland and on Taiwan, 1943-1958.” The Australian Journal of Chinese Affairs, vol. 24, no. 24, 1990, pp. 121–41, https://doi.org/10.2307/2158891.

Chang, Kai and Fang Lee Cooke. “Legislating the right to strike in China: Historical development and prospects.” Journal of Industrial Relations 57 (2015): 440 - 455.

Victor D. Lippit (2005) The political economy of China's economic reform, Critical Asian Studies, 37:3, 441-462, DOI: 10.1080/14672710500200474

Luo, Xubei, and Nong Zhu. “Rising Income Inequality In China: A Race To The Top.” Policy Research Working Papers (2008): n. pag. Web.

Choe, J. (2008). Income inequality and crime in the United States. Economics Letters, 101(1), 31–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econlet.2008.03.025

Lippit, Victor D. “The Great Leap Forward Reconsidered.” Modern China, vol. 1, no. 1, 1975, pp. 92–115. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/188886. Accessed 9 Jan. 2024.

Sullivan, D., Moatsos, M., & Hickel, J. (2023). Capitalist reforms and extreme poverty in China: unprecedented progress or income deflation? New Political Economy, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/13563467.2023.2217087

Allen, R.C., 2017. Absolute poverty: when necessity displaces desire. American economic review, 107 (12), 3690–3721.

Drèze, J., and Sen, A., 1989. Hunger and public action. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Hans-Günther Heiland; Louise I. Shelley; Hisao Katō (1992). Crime and Control in Comparative Perspectives. Walter de Gruyter. p. 245. ISBN 3-11-012614-1.

https://www.nytimes.com/1990/08/14/world/chinese-said-to-kill-450-tibetans-in-1989.html

https://web.archive.org/web/20170616053845/http://www.china.org.cn/english/13235.htm

https://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/deng-xiaoping/1989/140.htm

http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/asia-pacific/8057762.stm

https://archive.ph/9LOFr

https://www.gov.cn/gongbao/shuju/1989/gwyb198911.pdf

https://nsarchive2.gwu.edu/NSAEBB/NSAEBB16/docs/doc12.pdf

Meisner, Maurice (1998). The Deng Xiaoping Era: An Inquiry into the Fate of Chinese Socialism 1978-1994. Science and Society 62 (2):308-310.

https://books.google.com/books?id=F_zWHMFLQa4C

Greenhalgh, Susan (2005). Governing China's Population, From Leninist to Neoliberal Biopolitics. Stanford University Press

Hesketh T, Lu L, Xing ZW. The effect of China's one-child family policy after 25 years. N Engl J Med. 2005 Sep 15;353(11):1171-6. doi: 10.1056/NEJMhpr051833. PMID: 16162890.

https://www.nytimes.com/2018/03/01/business/china-parliament-billionaires.html

https://www.nytimes.com/2017/03/02/business/china-wealth-rich-parliament.htm

China’s Richer-Than-Romney Lawmakers Reveal Reform Challenge - Bloomberg

Mao Zedong on Deng Xiaoping (Peking Review, April 2, 1976)

Deng Xiaoping, “We Shall Draw On Historical Experience and Guard Against Wrong Tendencies”

Liu Shaoqi, “Instruction to An Tzu-wen and others,” January 23. 1950, quoted in The Struggle Between the Two Roads in China's Countryside, (Peking: Foreign Language Press, 1968,) p.4.

Lui Shaoqi, “Report Concerning the Question of Land Reform,” Selected Readings, (Japan: Chinese Culture Service Publishers, 1967) p.283.

Deng Xiaoping: Adhere to the Party Line and Improve Methods of Work (marxists.org)

Deng Xiaoping: With Stable Policies of Reform and Opening To the Outside World, China Can Have Great Hopes For the Future (marxists.org)

Jiang Zemin, who guided China's economic rise, dies | AP News

Xie Y, Zhou X. Income inequality in today's China. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014 May 13;111(19):6928-33. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1403158111. Epub 2014 Apr 28. PMID: 24778237; PMCID: PMC4024912.

Wall, Winter (2009) "China’s Infanticide Epidemic," Human Rights & Human Welfare: Vol. 9: Iss. 1, Article 51.

An informative article. The opening of China to foreign investment was a clearcut way to change the country and weaken socialism in China given global economic landscape.