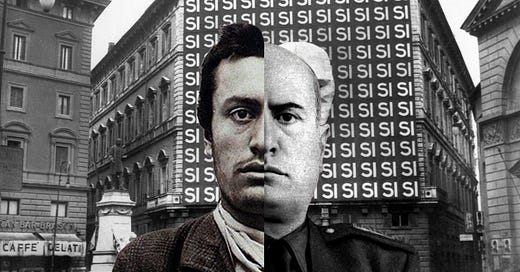

Benito Mussolini, the Prime Minister of Fascist Italy from 1921 to 1945, known more infamously as “Il Dulce”, who rose to prominence as a member of the Italian Socialist Party, and fell as the Head of the Salo Republic, Mussolini is remembered today as one of countless classical Caesarist dictators of the 20th century. He lives in popular consciousness as the leader of the March on Rome in 1920, and Hitler’s lapdog during World War 2, but this is not all there was to the infamous dictator.

The Socialist Years

Mussolini joined the Italian Socialist Party (PSI) in 1912, a part of the pro-Bolshevik wing, quickly becoming editor of “Avanti!” and was known as one of the most well-read socialists within the PSI, quoting from even the most obscure works of Marx which even few Marxists had ever read. At the dawn of World War 1, tensions sharpened between Italian socialists, with some known as the “Defencists” and others as “Interventionists”. The Defencists sought to fight against entry into World War 1, while the Interventionists bravely argued in favor of entry into the war against the Central Empires.

On this basis, Mussolini left the PSI’s paper, “Avanati!”, as the official “Avanti!” stance was anti-war and was shortly thereafter expelled from the PSI at the tail end of 1914 for inciting riots and violent revolution. Later on, Vladimir Lenin would refer to Mussolini as “a first-rate man who would have led our party to power in Italy [1]”, “the only one among you with the mind and temperament to make a revolution [2]” as well as “but a Socialist able enough to lead the people through a revolutionary path [3]”.

Soon, Mussolini would form his own “Autonomous Leagues of Revolutionary Action”, which would merge into another entity, the Revolutionary League of Internationalist Action, an organization of revolutionary syndicalists who had come together from the Italian Syndical Union in favor of intervention in the war. This merger formed the “Leagues of Revolutionary Action”, soon 9,000 members strong. In 1915, most of the members of the Leagues of Revolutionary Action joined the war effort. By 1919, when the World War ended, the Italian socialists within the movement, including Mussolini, returned home, meeting together in the Piazza San Sepolcro.

There, in the Plazza, the platform of “Sansepolcrismo” became realized as the basis for a new organization, the Italian Combat Leagues, or the “Italian Fasci di Combattimento”, which proposed a profound progressivism, arguing for universal suffrage, lowering the voting age, the formation of national technical councils, the implementation of a minimum wage, the establishment of a national militia, the nationalization of all arms factories, and a progressive tax on all wealth [4]. Mussolini even supported the progressive venture of Gabriele D’Annunzio and Alceste De Ambris in the annexation of the city of Fiume, which eventually became its own independent zone for a period of a few years. At this point, he was able to gain the support of not only many workers, but industrialists as well [16].

Mussolini’s Rise & Fall

Even this early on however, Mussolini’s unfettered opportunism shown through. Upon the questioning of his leadership from some fascists in 1920, Mussolini, rather than responding with reassurance to his members, stated “Can fascism do without me? Of course, but I too can do without fascism” [5]. In 1921, the National Fascist Party was formed, with the progressive futurists largely marching out of the movement, such as Carlo Carrà and Wladimiro Tulli, as the Party was organized as a part of the National Bloc, a move to a right-wing stance, completely shifting away from the original left-wing orientation which Mussolini fought for.

When the March on Rome came, the King, rather than cracking down on Mussolini’s Blackshirts via the armed forces, welcomed the new fascists in, giving them a task of creating a new coalition government. And just like that, Mussolini’s anti-monarchism collapsed, as he would later comment [6]:

How could one attack the Monarchy which, far from barring the doors, had flung them wide open? The King had effectually revoked the State of Siege proclaimed at the last moment by Facta; he had ignored the suggestions of Marshal Badoglio (or those attributed to him) which provoked a very violent article in Il Popolo d’Italia; he had given me the task of forming a ministry which — by excluding those Leftists still in the grip of anti-Fascist bias — was born under the signs of complete victory and national concord. If we had suddenly given a Republican character to the March, it would have complicated matters.

Mussolini, Story of a Year

Mussolini would soon become the Prime Minister of Italy, and on November 25th of 1922, Mussolini achieved full powers in the fields of administration and taxation until December 13th of 1923 to “restore order” to Italy [11].

Between 1925 and 1926 a mix of new laws was introduced into the government which eroded democracy within Italy. Law no. 2263 gave the Executive power over all other aspects of the government, with the legislative branches power drastically diminished [7]. In Law 237, signed February 26th of 1926, elective bodies in small towns were suppressed, and the new Podestà was established, appointed over a municipality directly by governmental decree [13] [14]. Through Royal Decree 1910, signed September 3rd of the following year, this was extended to all municipalities within Italy [8].

Although there was considerable development within Italy by the 1930s, Mussolini’s rule was wrought with compromise beyond the retainment of the Monarchy. In 1929, the Lateran Treaty was signed, and the Vatican officially became its own city-state, with Catholicism recognized as the national religion of Italy, and ensured that not only would land not be expropriated from the Church, but they would not be allowed to be subjected to taxation by the State either. On top of this, they would in fact acquire a substantive portion of land from the city of Rome, and marriage and divorce laws were made to be in alignment with those decreed by Church ordinance, a massive step backwards in civil society, although in fairness to history, these marital laws were never upheld in practice, amounting to lip service to the Catholic authorities [15].

Although opposed to radical racialism and antisemitism early on in his career, by 1938, at the dawn of World War 2, and at the behest of Adolf Hitler, Mussolini backpedaled on yet another one of his positions, and saw it fit to establish a series of race-laws in Italy, which cemented multiple measures against the Jewish people and African Italians, as well as subjects of Italian colonies.

By 1943, Italy split into two, and Mussolini was only left with the Italian Social Republic of Salo. In Salo, Mussolini, with nothing left to continue to lie for, attempted to return to the old Sansepolcrist line of thought he and others had thought up amongst each other in the years preceding his rise to power. Mussolini promised now to abolish the monarchy, to condemn the King, to establish an elective democratic system of representation, and turn housing into a human right. However, by now, it was far too late. Mussolini had entered his nation into an unwinnable conflict and there was no turning back. Disregarding all of the mistakes, the affirmation of the Monarchy, the implementation of racialist laws, the legislation of marriage on an anti-secular basis, the backsliding of the democratic process, the special privileges given to the Catholic Church, the pact with Hitler was the final nail in Mussolini’s coffin.

Mussolini’s rule (although he did succeed in transforming Italy from a backwards, agrarian, semifeudal state, the “soft underbelly of Europe”, into a relatively powerful nation) ultimately amounted in large part to a series of broken promises, concessions, and lies. He broke his promises on his anti-monarchism, on his anti-clericalism, on maintaining the democratic process, and finally he failed to maintain an Italy for all Italians. What we find here is neither a progressive, nor a reactionary form of governance, but rather the first time in recorded history where what had the potential to become a swan, instead devolved back into a lizard.

Sources

Rangel, Carlos. Third World Ideology and Western Reality: Manufacturing Political Myth. Translated by the author with the assistance of Vladimir Tismaneanu, Ralph van Roy, and María Helena Contreras, Transaction Publishers, 1986.

Farrell, Nicholas. Mussolini: A New Life. Independently Published, 2018.

Erik Norling, Lisbon, Revolutionary Fascism. Finis Mundi Press, 2011.

De Felice, Renzo. Mussolini il fascista: La conquista del potere. Page 151.

Mussolini, Benito. Story of a Year. 1944.

Gentile, Emilio. Storia del fascismo. Editori Laterza. 2022.

A gay island community created by Italy's Fascists - BBC News

Agreement Between the Italian Republic and the Holy See (lu.lv)

A cheeky opinionated piece failing to address the why of the matter in every matter addressed. Nevertheless a churlishly clever essay. This Romanesque Norman gives it one some way up.

It's "Il Duce," not "Il Dulce." Dulce means sweet or candy.